George Frederick Watts Biography In Details

Early years

George Frederic Watts was born in Marylebone, London, the delicate son of a poor piano-maker. He showed promise very early, learning sculpture from the age of 10 with William Behnes and enrolling as a student at the Royal Academy at the age of 18. He came to the public eye with a drawing entitled Caractacus, which was entered for a competition to design murals for the new Houses of Parliament at Westminster in 1843. Watts won a first prize in the competition, which was intended to promote narrative paintings on patriotic subjects, appropriate to the nation's legislature. In the end Watts made little contribution to the Westminster decorations, but from it he conceived his vision of a building covered with murals representing the spiritual and social evolution of humanity.

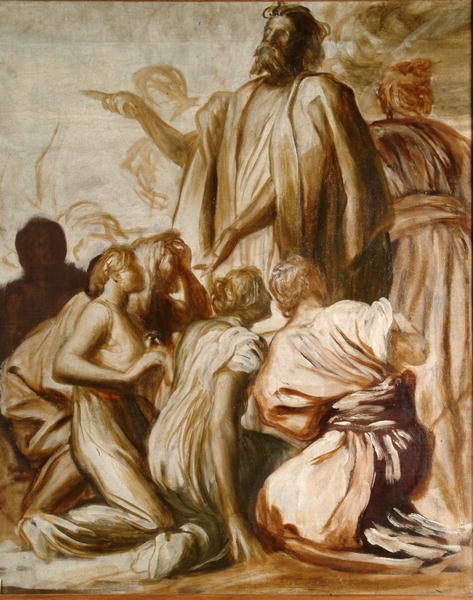

Visiting Italy in the mid-1840s, Watts was inspired by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel and Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel, but back in Britain he was unable to obtain a building in which to carry out his plan. In consequence most of his major works are conventional oil paintings, some of which were intended as studies for the House of Life.

Little Holland House in Kensington

In the 1860s, Watts' work shows the influence of Rossetti, often emphasising sensuous pleasure and rich color. Among these paintings is a portrait of his young wife, the actress Ellen Terry, who was nearly 30 years his junior - just seven days short of her 17th birthday when they married on 20 February 1864. When she eloped with another man after less than a year of marriage, Watts was obliged to divorce her (though this process was not completed until 1877). In 1886 at the age of 69 he re-married, to Mary Fraser-Tytler, a Scottish designer and potter, then aged 36.

Watts's association with Rossetti and the Aesthetic movement altered during the 1870s, as his work increasingly combined Classical traditions with a deliberately agitated and troubled surface, in order to suggest the dynamic energies of life and evolution, as well as the tentative and transitory qualities of life. These works formed part of a revised version of the house of life, influenced by the ideas of Max Muller, the founder of comparative religion. Watts hoped to trace the evolving "mythologies of the races [of the world]" in a grand synthesis of spiritual ideas with modern science, especially Darwinian evolution.

In 1881, having moved to London, he set up a studio at his home at Little Holland House in Kensington, and his epic paintings were exhibited in Whitechapel by his friend and social reformer Canon Samuel Barnett. Refusing the baronetcy offered him by Queen Victoria, he later moved to a house, "Limnerslease", near Compton, south of Guildford, in Surrey.

After moving into "Limnerslease" in 1891, Watts and his wife Mary arranged the building of the Watts Gallery nearby, a museum dedicated to his work - the first (and now the only) purpose-built gallery in Britain devoted to a single artist - which opened in April 1904, shortly before his death. Watts's wife Mary designed the nearby Mortuary Chapel. Many of his paintings are also held at the Tate Gallery - he donated 18 of his symbolic paintings to the Tate in 1897, and three more in 1900. He was elected as an Academician to the Royal Academy in 1867 and accepted the Order of Merit in 1902.

Late paintings

In his late paintings, Watts' creative aspirations mutate into mystical images such as The Sower of the Systems, in which Watts seems to anticipate abstract art. This painting depicts God as a barely visible shape in an energised pattern of stars and nebulae. Some of Watts' other late works also seem to anticipate the paintings of Picasso's Blue Period.

Watts was also admired as a portrait painter. His portraits were of the most important men and women of the day, intended to form a "House of Fame". Many of these are now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery - 17 were donated in 1895, with more than 30 more added subsequently. In his portraits Watts sought to create a tension between disciplined stability and the power of action. He was also notable for emphasising the signs of strain and wear on his sitter's faces. Sitters included Charles Dilke, Thomas Carlyle and William Morris.

During his last years Watts also turned to sculpture. His most famous work, the large bronze statue Physical Energy, depicts a naked man on horseback shielding his eyes from the sun as he looks ahead of him. It was originally intended to be dedicated to Muhammad, Attila, Tamerlane and Genghis Khan, thought by Watts to epitomise the raw energetic will to power. A cast was placed at Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town, South Africa honouring the grandiose imperial vision of Cecil Rhodes. Watts' essay "Our Race as Pioneers" indicates his support for imperialism, which he believed to be a progressive force. There is also a casting of this work in London's Kensington Gardens, overlooking the north-west side of the Serpentine.

Several reverent biographies of Watts were written shortly after his death. With the emergence of Modernism, however, his reputation declined. Virginia Woolf's comic play Freshwater portrays him in a satirical manner, an approach also adopted by Wilfred Blunt, former curator of the Watts Gallery, in his irreverent 1975 biography England's Michelangelo. On the centenary of his death Veronica Franklin Gould published G.F. Watts: The Last Great Victorian, a much more positive study of his life and work.

Blunt was succeeded as curator of the Watts Gallery by Richard Jefferies, one of the foremost authorities on Watts, who retired at the end of March 2006, to be replaced by Mark Bills. (From Wikipedia)